The key issues across Western Australia’s custodial estate

Each year the Office’s Annual Report highlights key issues and challenges impacting the custodial estate in Western Australia. The following issues were raised in the 2024-2025 Annual Report.

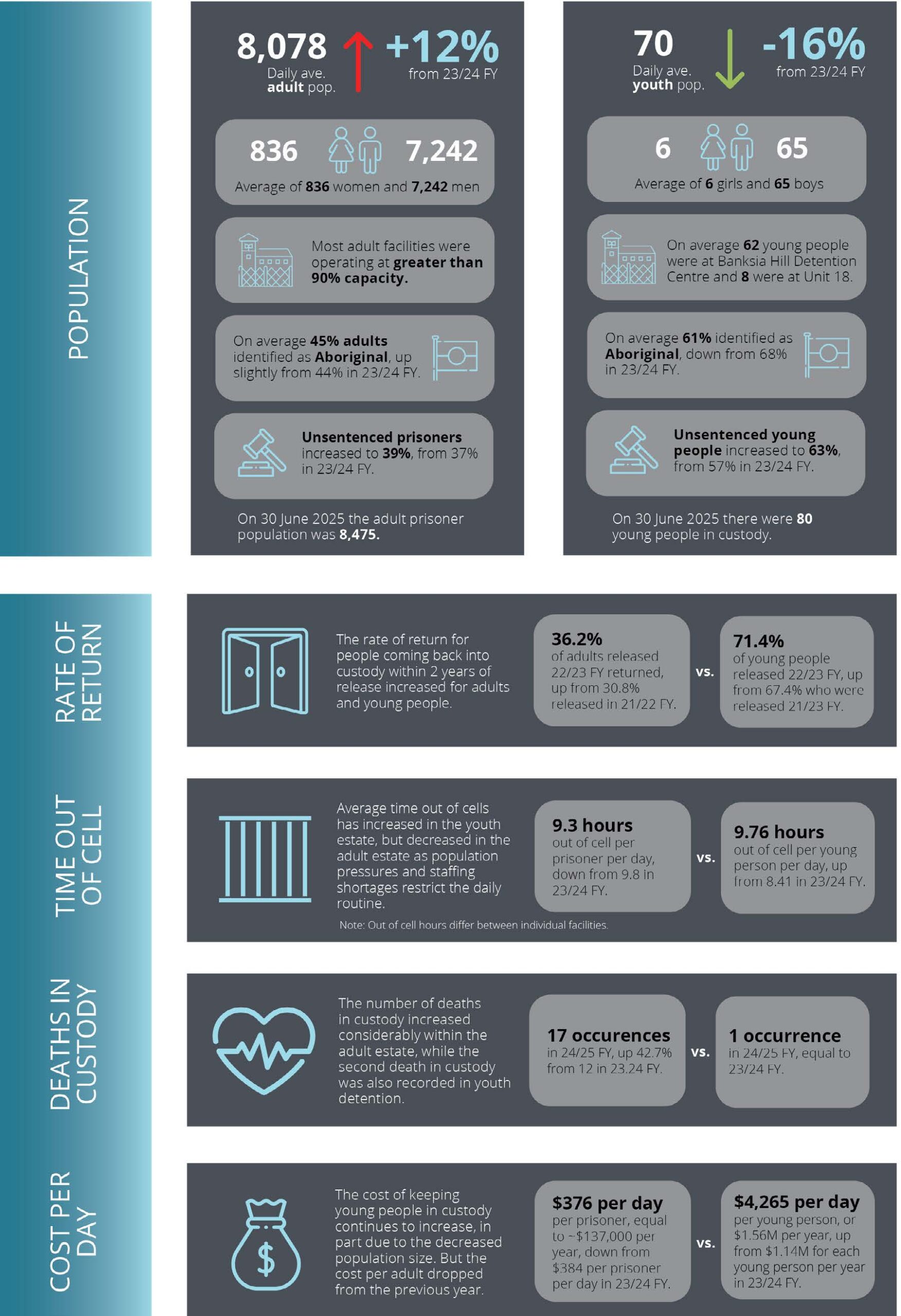

The Western Australian prison population has increased rapidly over the last year and prisons have become severely overcrowded. Many facilities have operated above their general bed capacity which has meant hundreds of people have been sleeping on the floors of cells not designed to accommodate them. Over the year, the average daily population rose by 12% to 8,078, but that does not tell the true story. This is because the total population is continuing to rise rapidly. On 1 July 2024, the adult population was 7,800. By 30 June 2025, this figure had surged to 8,475, an 8.7% total increase in just one year. The biggest increase was in the number of First Nations women (up 16.6%). The average number of people held on remand had also grown between financial years (from 37% of the population to 39%).

At the same time there have been significant challenges with staff shortages across facilities and services, both custodial and non-custodial alike. We are currently conducting two reviews – into non-custodial staffing shortages, and workers compensation rates – highlighting the reasons for and impacts of these shortages. Both reviews are due for tabling in the 2025-26 reporting period.

However, our ongoing monitoring of the custodial estate has found the impact of the increased population, coupled with insufficient staffing, is pervasive. It effects every aspect of a person’s custodial journey. This includes, at the most basic level, their time out of cell and how many people they must share that cell with (OICS, 2025) – as at 30 June 2025 there were 373 men and 33 women sleeping on a mattress on the floor of a cell that is often already occupied by two or more prisoners. It also impacts the quality and frequency of contact they have with their loved ones, with too many people vying for limited phones and visit sessions regularly cancelled because there are not enough supervising staff (OICS, pending 2025C). The impact becomes more insidious affecting people’s rehabilitative and reintegrative opportunities, as their initial assessments and management plans are consistently delayed (OICS, pending 2025D). These delays prevent people in custody from accessing programs and services to help them address their offending and their addictions; and build capacity and skills to improve their chances of success upon release.

It also reduces their release options which contributes to the population pressures as they are often ineligible for parole having not addressed the underlying reasons for their offending.

Population and staffing pressures also significantly affect the general safety and security of custodial facilities. The number of recorded attempted suicides within the prison population increased from 62 in 2023-24 to 72 in 2024-25. Similarly, the number of prisoner-on-prisoner assaults grew by more than 200, increasing the rate of victims per 100 prisoners from 12.3 in 2023-24 to 13.9 in 2024-25. Insufficient staffing can compromise security capacity which has also manifested in the reduced number of searches conducted of adults in custody, despite the significantly increased population (searches decreased by 1,554 in 2024-25, down from 532,367 in 2023-24).

For the immediate future there does not appear to be a pressure release valve. The remand and imprisonment rates are outside the Department’s control. However, the Department has continued to try address the ongoing staff shortages with ongoing recruitment of custodial staff and by convening a working group to develop recruitment and retention strategies in clinical and professional roles. Although this has been a positive strategy, attrition rates remain high and therefore this initiative must be sustained into the future. The Department is also considering options, through short, medium, and long-term planning, to increase bed capacity, including opportunities for in-fill within existing facilities and medium-term expansion. Both, we are told, are designed to buy time for decisions around a larger expansion.

In the last 12 months, several factors including access to crisis care, incidents of self-harm, the number of people in custody with a psychiatric condition (p-ratings), and deaths in custody have contributed to our growing concern about mental health in the custodial estate.

Our review examining access to crisis care, for example, found crisis care units are under significant pressure to meet demand due to a variety of factors (OICS, 2025B). These include outdated infrastructure and a growing number of people in custody who are at risk of suicide or self-harm. These are exacerbated by low staffing across mental health streams including nursing, counselling, and psychiatry which cannot provide thorough support – a finding which is also highlighted in the upcoming release of our review into non-custodial staffing (OICS, pending 2025C). It suggests the need for the Department, and the State Government, to consider whether mental health services in prison, and perhaps health services more generally, should be managed by the Department of Health as occurs in other Australian jurisdictions.

We have observed an increased frequency of self-harm and attempted suicide incidents over the last year with more than 2,000 recorded minor or serious incidents for adults and young people (a rate of 26.5 per 100 people in custody). Serious self-harm incidents (those requiring ongoing medical treatment or overnight hospitalisation) have become an increasing concern with a 50% increase (to 9 incidents) in the first quarter of 2025 (compared to the same time in 2024 when just 6 incidents were recorded). In 2024, there were also seven deaths from apparent suicide which represented the highest cause of death in custody. Deaths from apparent suicide increased 75% from the previous year (4) and by 250% compared to 2022 (2).

P-ratings, which are assigned to people in custody with a diagnosed mental health condition or awaiting assessment, highlight where mental health or specialist forensic mental health services are needed. In the past year, the number of people with p-ratings has remained stable despite the increase in daily average population. Acacia, Bandyup, Casuarina and Hakea prisons accommodate the highest number of people with these classifications. However, as highlighted in our review of crisis care access, there are limited resources to provide psychiatric care for people in custody. The Frankland Centre, the state’s only forensic hospital which treats people in custody who have psychiatric condition, only has 30 beds available and can only accommodate around 10 patients from prisons at any one time. Consequently, many people in custody sit on the waiting list and are held in untherapeutic conditions awaiting treatment.

In December 2024, we released our follow-up report to the 2023 inspection of youth custodial facilities. It documented significant progress in restoring safe staffing levels, implementing a new model of care, upgrading physical security, establishing an Aboriginal Services Unit, implementing a new teaching model in the school, and the health department establishing a new neuropsychology and mental health team within Banksia Hill Detention Centre. Out of cell hours, and access to education, visits, and an expanded range of programs, supports, and recreation activities had all improved. These positive trends have broadly been sustained since then. And there has been impressive progress embedding cultural safety for First Nations young people in practices at Banksia Hill and engaging Elders and others with young people in detention.

However, it was still the case that psychologists were having to support so many at-risk young people they were unable to deliver offence specific counselling for others. Nor did case planning have the resources needed to offer a comprehensive individual case management service to young people.

Tragically, and despite the improvements seen, in August 2024, a second young person died in youth detection. This occurred at Banksia Hill at a time when it appeared to be functioning relatively well. A Coronial Inquest into the circumstances of his death has yet to begin. However, the current year was marked by extended coronial hearings relating to the 2023 death of Cleveland Dodd in Unit 18. Findings and recommendations from this inquest are expected by the end of 2025.

Despite improvements seen across the year at Banksia Hill, there has been a continuation of serious incidents involving roof ascents, infrastructure damage, and assaults on staff. The Department has deemed it necessary to keep Unit 18 open despite calls from this agency and many others for its closure. Unit 18 has, despite all of its shortcomings, provided a more supportive and therapeutic environment for many of those placed there, and for some young people it is preferred over Banksia Hill. The resources to maintain Unit 18 are considerable and as Banksia Hill continues to upgrade its infrastructure, it may soon become possible to replicate the intensity of these supports in the more secure areas within Banksia Hill.

In the meantime, considerable progress has been made in constructing a new Crisis Care Unit within Banksia Hill and planning for a new detention facility to replace Unit 18 has commenced. The Inspector has been invited to be an observer on the Community Consultative Advisory Committee for this new facility.

We have published 11 reports over the last financial year which included 115 recommendations seeking to improve practice, update policy, and reduce risk. Our current Memorandum of Understanding with the Department establishes the level of acceptance for our recommendations. To some extent, the Department has supported 86% of recommendations with only eight not supported. This level of support has increased since 2023-24 (83%). One recommendation was not targeted at the Department and, therefore, did not receive a level of support.

Over the last year, the greatest proportion of our recommendations can be categorised as relating to human resources and prison management (26%). These recommendations seek to address issues in staffing levels, staff training, staffing structure, or may relate to the people or positions managing the facility.

We made the second largest number of recommendations in respect to the adequacy of infrastructure. These recommendations seek to improve the adequacy of building or specific spaces, including cells (14%). This might also include design, sizing, and building conditions.

More than one in 10 recommendations related to facility protocols, policies, and procedures (11%). Often these regarded the development or revision of policy to meet contemporary best practice.

Page last updated: 17 Nov 2025